How to make chocolate 4,000 years ago – Guatemala

Although cacao has been consumed for over 4,000 plus years in the Americas, processed chocolate is a new concept to indigenous communities and is a product of Europe. I have spent the last many years learning about chocolate using European methods, but on my trip to Guatemala I went as far back as anyone can possibly go when it comes to making chocolate or consuming cacao.

Before Mexico was Mexico and Guatemala was Guatemala there was Meso-America and Maya territory. Southern Mexico and all of Guatemala belonged to the Maya. And the Maya of Guatemala have held on to their strong culture of consuming cacao. Yes, Mexico has a strong link to cacao as well but different. In Oaxaca City you can see cacao beans and cacao drinks sold in every market but cacao doesn’t grow in Oaxaca City. So there is that huge gap. In Guatemala you will also see cacao beans and drinks sold at the markets but they actually grow that cacao themselves. They have a direct connection. Guatemala is also the home to the most cacao relics in the world.

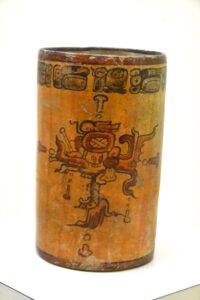

Before I arrived to Alta Verapaz, I made a quick stop in Guatemala City. I realized there was a Popol Vuh museum there and since I had read the Popul Vuh in college, the book of the creation and history of the Maya people, I knew there would be some interesting cacao and chocolate things to find there. Please visit this museum if you are in Guatemala City! It has some great cacao pieces.

Chances are you have never had a chocolate bar made with cacao from Guatemala. Which is ironic. The Maya of this region dominated cacao trade for thousands of years up to a few hundred years ago. As a comparison, Europe discovered cacao 500 years ago.

Even though the Maya are masters of cacao, they don’t know chocolate very well. If you visit the home of most Mayans in the mountains or villages, you will see that they still work with tools that were used before Europeans discovered these lands; metates and molcajetes.

Most Maya communities are rural, buried deep in mountainous villages, difficult to get too, and are lacking many modern resources. I visited the Alta Verapaz region with the goal of teaching women to work with chocolate. When I left the USA I had a great plan and an agenda for what I would be teaching. I even made a power point presentation.

When I arrived to Guatemala I realized the village had no electricity. Ignorantly, I had not planned for that. I tried my best and channeled my mother who still, in the modern age, cooks outside on clay ovens and uses molinos and rocks to prepare food.

The only reason chocolate is as you know it, creamy and in the shape of bars, is because of machines, large machines with powerful motors that force the cacao to do things that the human body cannot make it do. The only reason Europe emerged as the best chocolate maker is because of the industrial revolution. So how do you teach a village to make chocolate without electricity and machines? Below is my attempt.

Step 1: Find cacao. Usually when you are in the USA finding cacao is the biggest challenge, whereas everyone in this village has cacao trees in their garden and process small batches for personal use. They harvest about 8 pods at a time and ferment the seeds in a basket or wrapped in banana leaves for 3 days. After fermentation they wash the pulp off and pride themselves on having “clean looking” beans. They set them to dry on banana leaves in direct sunlight until they look dry. From several women we were able to accumulate 5 kilos of dried beans.

Step 2: Roast. My home oven has a thermometer and fan because roasting cacao requires a delicate balance of time and temperature. Most chocolate makers make many batches when working with new cocoa beans to get the best combination. In Guatemala there are clay comales above firewood and 5 kilos that took the women a few months to grow, ferment, and dry. No test batches allowed. We built a fire and once most of the smoke clears, we set the cacao directly on the stove.

Since it is in direct contact with heat we must constantly keep it in motion. They use sticks or bundles of tied fibers to keep the cacao in motion. It begins to pop, turn dark, and the smell of chocolate now overpowers the smell of firewood. We also put the cinnamon sticks and vanilla pods to heat, which also came directly from their gardens.

Step 3: Crack and winnow. I have seen commercial winnowers, hair dryers, vacuums, and natural air used to blow the husk from the nibs … but I have never seen a group of women gather socially to peel each bean one by one. They tell me this is when they gossip. Before a wedding, festival, funeral, or any village event, the women all gather to toast and peel the cacao beans. It takes them hours, sometimes days depending on the event. They say that every village event must have a cacao drink but that the drink varies depending on the event. I introduce them to the concept of cracking them on a rock with another rock using the ubiquitous metate. They don’t seem convinced but I show them how much quicker it can be, then we use a fan made of palm leaf to remove the husks.

Step 4: Grind. Everyone owns a molino, a counter top tool with two metal disks grinding against each other (mill). We have to give it two passes with sugar to give it the smoothest consistency. But it is a slow process. I was told about a large molino in town powered by a gas motor that is used to grind corn for masa. They charge 5 cents per grind. We walked over to visit and ask the owner if we can test a batch of cacao and sugar and he laughs because the notion is so ridiculous.

After some convincing he allows one run. We pour our cacao nibs into the hopper and passes through the machine spectacularly; we begin to add sugar slowly … and the entire machine comes to a hard halt. We quickly thank him and take our things and leave. He was right. Not the right machine to make chocolate. We now know to mix the sugar with the ground cacao only at the end, once it’s in the bowl, and not put it in the molino at all.

Step 5: Add flavors. Ground cacao and sugar was our base. I asked everyone to gather ingredients from their gardens to mix with chocolate. They returned with coconuts, oranges, cardamom, vanilla bean, cinnamon bark, mint leaves, peanuts, ginger, and pepper.

We heated the chocolate in calabash bowls (something like a coconut shell) and “tempered” in cooler bowls. We made bark and balls of chocolate and let them cool in the shade.

The chocolate was strong and full of flavor. It was beautiful and rustic. They had never understood the process of chocolate making until now. But, this was not what they expected; they wanted a sort of Hershey’s bar. They wanted me to process it further and make it smooth and creamy. But that required many more machines.

The ironic thing was that I was there to teach them about chocolate but I ended up learning more than they did. Three times per day they gave me a cacao drink and each time it was different. And all were named cacao drink. Some of the recipes were:

The ironic thing was that I was there to teach them about chocolate but I ended up learning more than they did. Three times per day they gave me a cacao drink and each time it was different. And all were named cacao drink. Some of the recipes were:

- Cacao, water, sugar, corn masa.

- Cacao pulp, water, sugar.

- Cacao liquor that had been sitting in water for a few days fermenting, water, cacao nibs, sugar.

- Cacao, toasted ground corn, water, sugar.

- Corn masa, water, cacao, sugar (atole).

They wanted me to make a product they considered modern, while chocolate makers in the US and Europe are trying to create products that are more rustic, contain higher quantities of cacao, and that take us back in time.

I visited the Alta Verapaz community before it had set up its cacao processing plant which is managed by Uncommon Cacao. Greg, from Dandelion Chocolate visited about a year after me and he was able to capture a more technical take on the group: Dandelion Alta Verapaz Cahabón blog post.